Leaning and Cruise Flight

Efficiency

I fly behind a

3100cc Corvair engine in my highly modified KR2S, N56ML, which now has almost

800 hours on it.† Itís not the cleanest

KR youíll ever see, since it doesnít even have paint on it yet, and has a lot

of rough edges, but I still manage to get fuel economy numbers like

48 miles per gallon while flying at 157 mph true airspeed (TAS), with a top

speed of over 190 mph.† And since I burn

93 octane auto fuel almost exclusively, this means I can fly a lot cheaper than

I can drive my Volkswagen.† And I donít

have to worry about traffic or state troopers, the view is a whole lot nicer, I

arrive about 3.5 times quicker, and I never have to stop for lunch!

†

†

Flying High -

How do I get such good fuel

economy?† Itís mostly due to aggressive

leaning while at high altitude, and generally keeping a close watch on my air/fuel

mixture from takeoff to landing.† I like

to fly high on cross-country flights (usually 9500í or 10,500í) because itís

smoother and about 30F degrees cooler up there, and the engine can be leaned

south of peak EGTs (exhaust gas temperatures) without risking cylinder head or

piston damage.† Running lean of peak at

altitude lowers EGTs considerably because at altitude the cylinders donít fill

as well due to the thinner air, and the inlet temperature is 30F degrees

cooler, so detonation is not going to happen.†

Also, I can glide about 22 miles with the engine shut down, and radio

signals travel at least 200 miles at that kind of altitude.† Why fly low when you can fly high?† Donít get me wrong, flying low and fast

around the patch is a real hoot, but thatís for days when Iíve only got a few

minutes before sunset and need a serious flying fix.† Iíve been known to drive home with a huge KR

grin on my face after one of those flights, and itís a pretty regular

occurrence!

Carb Heat - Another trick to great economy is using

carburetor heat to increase the carb throat temperature to about 110F degrees,

which improves the fuel distribution between cylinder head banks.† Adding carb heat while watching the EGTs

shows the EGT spread between cylinders becomes much closer. †As with aggressive leaning, this is not

something you want to do at full power and low altitude, because the higher

inlet temperatures will increase the likelihood of detonation, and at a time

when you can least afford it.† Detonation

is the almost instant spontaneous combustion of the air/fuel ratio in the

combustion chamber due to higher temperatures, higher pressures, or lower fuel

octane rating, rather than the usual controlled burn.† It is more likely at wide open throttle

settings, because the cylinders get filled with the maximum amount of air and

fuel, increasing the pressure and therefore, the tendency to detonate.† Thereís a pretty good ďhow toĒ on how to

build a carb heat box on my website at http://www.n56ml.com/corvair/airbox/

.

Detonation is something Iíve experienced about three

times now while flying.† So far Iíve been

lucky, and with the help of the EIS and air/fuel meter, recognized it

immediately, and in time to mitigate it before it got out of control and

damaged things.† William is rightÖyou

canít hear it while flying, but you can hear it (if you recognize it) on

takeoff if vapor lock has set in and the mixture becomes too lean to make the engine

happy.† Iím familiar with detonation mainly

because I keep pushing the envelope on burning 93 octane auto fuel with a high

compression ratio.†

The first time I

had engine detonation was on an extended ground run in my driveway, before I

ever took the airplane to the airport.†

For some crazy reason I thought I needed to prove that my engine would

run wide open for something like a half an hour, and proceeded to do that.† I was monitoring CHTs, but had the limits set

at something like 585F degrees, which is what the GM idiot light is set for

(thatís why they call it the idiot light!).†

When the alarm went off, it was too late, as Iíd melted the area around

the head gasket on cylinder number three, which is the one that runs the

hottest on my installation (as well as most others).† I could tell the engine was running rough,

and turning the prop over by hand revealed no compression on that cylinder, as

well as air escaping between the cylinder and head.† Time to resurface that head!† Fortunately getting the head off a Corvair is

about a one hour affair, because itís all out there in the open once the

cowling is off, and itís a pretty straightforward job.

So the lesson learned

there was to set my CHT alarm at 450F degrees, and donít sit on the ground

running wide open for more than a preflight check, or if longer maintain a very

close watch on CHTs.† Airplanes with

cowlings installed cool a LOT better flying than sitting on the ground,

especially slick KRs with small cowling inlets.†

My airplane with no cowling installed stays incredibly cool on the

ground, but thatís probably because I have plenums that force the propwash down

over the cylinders.

The few other times

Iíve experienced detonation involving very high ambient temperatures, and delays

in getting off the ground.† Because of

the cowling's small inlet size (which works fine at speed, and enables me to

minimize cooling drag), cooling on the ground is marginal on a very hot

day.† If Iím flying on a day in the high

90ís, stop in to refuel or pick up a passenger, and shut the engine off for a

few minutes, the engine ďheat soaksĒ while itís sitting.† So when I start the engine itís already hot,

then taxi out to the end of the runway, and it never really cools off.† Now wait for a plane or two to takeoff or

land, and then go full throttle on takeoff, and Iíve just met all the

conditions for detonation to occur.† Some

details on one of these detonation incidents, see http://www.n56ml.com/flights/detonation/

.

Autofuel - Keep in mind that this is entirely self-inflicted

on my part, since Iím running a 9.4:1 compression ratio, AND only burning 93

octane auto fuel.† The cure is simple

enoughÖeither run 100LL avgas or lower the compression, or both if you like the

belt, suspenders, and parachute approach.†

What Iíve learned to do is to burn a mixture of 25% avgas with auto fuel

when I know Iím going to get into a sticky situation such as takeoff at OSH or

SNF after idling for 20 minutes), and that raises the octane significantly

enough to get me out of the detonation danger zone.† Fortunately for me, flying to

Having said that,

let me mention that ďmogasĒ sold at FBOs is only required to be (and almost

always is) 87 octane fuel of unknown lineage.†

I never buy the stuff, for that reason and the fact that I trust the

fuel from the local Raceway more than Iíd trust that 500 gallon tank at the

airport that probably never sells any mogas.†

93 octane Raceway is exactly what I put in my fuel injected cars and my

airplane, and Iíve never had a problem with it.†

I hate to even admit this, but my plane has no means of draining water

from the tanks.† I built in fuel sumps

and drains, but when the vinylester cured, it somehow sealed them shut.† I tried to open one, and it stayed open and

leaked, so I drained the tank and JB Welded it shut the night before my first

SNF visit.†

3500 gallons of

Raceway fuel later, Iíve not found a single drop of water in my fuel tank or filters.† Call it a calculated risk, but Iím OK with

that statistical average regarding 93 octane from your favorite gas station.† Iím not saying do what Iím doing, but just

making the point that if youíre worried about the quality of fuel from your

local gas station, it might be needless fretting.

Autofuel has other

disadvantages, such as nasty chemicals that can damage carburetor parts and

composite fuel tanks, but Iíve had no problems with either of those on my

plane, and Iíve run about 3500 gallons of auto fuel through it up to now.† I did use vinylester resin to make my fuel

tanks, which was created for jobs like fuel compatibility.††

William Wynne will

also tell you that another downside of autofuel is that its vapor pressure is

higher than avgas, so itís easier to light off a fire with auto fuel vs

avgas.† That can be a life or death

difference in a crash, given the right (or wrong) circumstances.† I have no fuel in the cockpitÖ itís all out

in the wings, so I feel like thatís the mitigation factor in my case.† Unfortunately my fuel IS in the stub

wingsÖitíd probably be better in the outer wings from that standpoint, which

one hopes would be sheared off in a really bad crash, but not necessarily.

Vapor lock is another gremlin that can sneak up on

you.† The setup for vapor lock is very

similar to how you set yourself up for detonationÖand vapor lock can bring on

detonation easier than you might think, because the last thing you want on a

hot day, heat soaked takeoff is to have the mixture lean itself out because the

engine canít suck enough fuel!†

I was flying back

from Corvair Wings and Wheels one year in northern

†I started looking around for empty hangars and

found one wide open with no planes in it, and a toolbox with a big fan near the

workbench.† I told the kid in the FBO I

was going to borrow the fan if nobody minded, and he said ďno problemĒ.† I pulled cowling off and aimed the big fan at

the engine and started cooling it off.†

While I had access, time, and a toolbox at my disposal, I pulled the

fuel line off the carb, stuck it in a bucket (thanks dude) and it was just a

trickle!

I removed the

finest fuel filter and checked it just for grins and found zero contamination.† Then I checked the coarser filter prior to it

and found no contamination.†† By the time

the was all over the engine was pretty cool, thanks to the big fan blowing on

it, so I buttoned it up, quickly taxied out to the runway, and took off

again.† This time I watched the air/fuel

meter on takeoff and it showed a much richer mixture, so off I went toward home

with no other complications.† Vapor lock

strikes again!† Experience has now taught

me that taking off with a carb temp over about 105F is asking for detonation,

at least with autofuel and a 9.4:1 compression ratio!

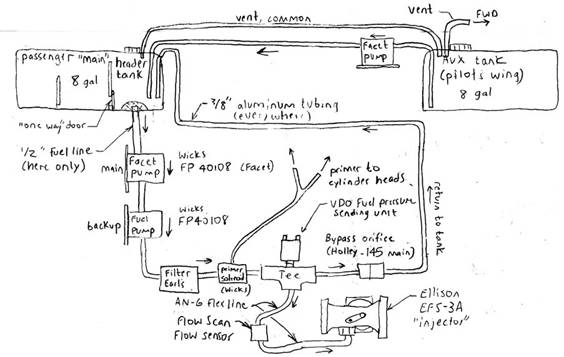

One thing Iíve done

to mitigate vapor lock is to build a return route into my fuel system, so the

fuel is constantly circulated through the engine compartment and back to the

tank.† I made a small doubled ended AN-6

fitting with an orifice in it that allows the fuel to keep moving, rather than

sitting in the line vaporizing due to heat.†

Of course Iíve also fire-sleeved all of my fuel and oil hoses, but this

fuel recirculation pays.† Thereís more on

how I made it, along with many other aspects of my fuel system on my ďfuel

systemĒ web page, at http://www.n56ml.com/fuel/.

One way to improve

fuel distribution on ďslide carbĒ installations is to add a ďCyclone Fuel SaverĒ.† Hoaky as it sounds, the FuelSaver is a

cylindrical gizmo that slides into the intake manifold just downstream from the

carb, and before the split in the manifold that leads to each cylinder head

bank.† It has twisted-up vanes that

impart a swirl and turbulence to the fuel/air charge, thereby making the

mixture more homogeneous by the time it reaches the split, so the mixture going

to each bank is more uniform.† And it

works!† It brought my EGT spread from

about 100F degrees down to about 50 degrees.†

I got the idea from Joe Horton, whoís also sold on it.† It does make a real difference in how far the

engine can be leaned before the leanest cylinder starts misfiring.† †Below

is a crude drawing of my fuel system, and where the bypass orifice is.

Speaking of ďslide

carbĒ installations, Iím not sure Iíd buy an Ellison again, partly for the

reason stated above, and partly because the mixture changes with throttle

setting.† Because I can monitor the

mixture so precisely with my air/fuel meter, I can detect much smaller mixture

changes than most folks, without staring at a bunch of EGT bars (although I

have those for reference also).† But for

all I know, other carbs may be no better.

EIS (Engine Information System) - I have six EGT probes and six CHT

(Cylinder Heat Temperature) probes, so I can keep close tabs on what each

cylinder is doing.† These probes are all

connected to a Grand Rapids EIS-6000 (Engine Information System) that updates

the display and writes to a data file once per second, which is then stored on

the laptop that I always fly with.† As a

result, I have a digital record of almost all engine parameters for most flights

that Iíve made in the N56ML. †I also

monitor and record manifold air pressure, carb throat temperature, fuel flow

rate, fuel pressure, under the cowling temperature, outside air temperature,

engine RPM, altitude, etc. †There are

other more expensive systems like the JPI that will store that same info to a

Compact Flash card or something similar, but since I fly with a laptop on cross

countries anyway (in order to have XM/WX weather and moving map sectional

capability), the EIS works fine for me.

†I try not to fly without the laptop though,

because recording every flight is very important to me.† I donít even bother filling in my flight log,

because I can go always go back and ďrecreate the crimeĒ with EIS flight data. †Itís very easy to count up the number of

landings for the log book, just by checking engine rpm and altitude.† If RPM drops below 1500, Iím landing, unless

Iíve shut it off at 12,500í for a glide test (and then I cross-check the

altitude column).† The serial output

option for the EIS was $9, last time I checked, and that included the connector

and wiring!

Air/fuel meter - I lean my engine by using an air/fuel

ratio meter that I paid about $40 for several years ago.† The oxygen sensor I use is an inexpensive

ďone wireĒ Bosch ďuniversalĒ O2 sensor, that costs about $20, and lasts one or

two hundred hours on average, since I burn mostly auto fuel.† 100LL works for maybe 50-100 hours before the

sensor needs replacement.† Thatís

insignificant compared to the price of fuel I run through the engine during

that time.† The meter is composed of a 10

segment bar LED thatís broken down into green (proper mixture), yellow (a

little rich or a little lean), and red (for way off).†

†I find this inexpensive air/fuel ratio indication

to be indispensable, and an invaluable safety warning device.† If I do something stupid with the mixture

knob, or something like vapor lock deprives the engine of fuel, the A/F meter

is the first thing to notify me.† Reaction

time on it is about one second, and one glance at it tells me if the mixture is

too rich, too lean, or just right.† It

also aids me in testing because it gives me a known mixture point that I can

use at different RPMs, altitudes, and speeds to compare factors such as the

effects of carb heat on fuel economy.†

For example, I can have the mixture leaned all the way out so that the

very bottom red LED on the meter is just flashing on and off, and when pulling

out the carb heat knob, the mixture goes up past stoichiometric (perfect 14.7:1

mixture) and well into the rich area.†

The RPMs drop a little also, but I can give it a little more throttle,

then lean it back out, and eventually end up getting better fuel economy, and

mixture distribution between cylinders, while burning less fuel, but still

turning the same RPMs as before adding carb heat.† For more on this air/fuel meter setup, see http://www.n56ml.com/corvair/o2meter

.

Ground runs - Call me crazy, but when I rebuild an

engine, I might run it for a minute or two wide open during the early morning

or when temps are cool, but thatís all.†

If itíll run 30 seconds on takeoff, Iím high enough to come back to the

field.† First flights need to be done

with that attitude in mindÖtake off, climb around the pattern, and keep the

airport under you until a few minutes of climbing at wide open throttle

convinces you that your engine rebuild was successful.

Of course thereís

no substitute for running it on an engine stand with something like William

Wynneís ďground-basedĒ cooling shrouds that guarantee sufficient cooling while

allowing the engine to be broken in and proven while youíre standing safely on

the ground.

Takeoff - I rarely take off with the carb set on

full rich, except in the wintertime.† The

air fuel ratio meter tells me that in the winter the Ellison carb is set just

right for the cold temperatures of wintertime.†

In the summer, if I donít tweak the mixture screw down on the carb about

an eighth of a turn, the carb will run too rich at wide open throttle.† Since Iím lazy and donít bother, I just donít

run the mixture all the way in during the summer months.† Well, itís not that I have to remember that

summer/winter businessÖI just set the mixture wherever the meter tells me.†

Thatís a bit like

the folks that worry about whether or not they can handle a counterclockwise rotating

engine on takeoff as opposed to a clockwise engineÖwhen it starts to drift off

to the side of the runway, youíll give it whatever rudder is necessary to keep

it from happening, regardless of whether itís left or right.† So essentially, thereís no difference.

My runup is a pretty simple

matter.† I just wait until the oil temp

is warm enough to fly (my personal limit is about 80F, but most would consider

that too low), and I run it up to full throttle for a second or two to make

sure I can get max rpm (right at 3000 rpm with my current Sensenich 54Ēx58Ē

prop), swap ignition systems back and forth to make sure itíll run on either

one, check oil pressure, and go down the runway.

I canít talk about

instrumentation without mentioning the DynaVibe.† This is an inexpensive ($1500) tool thatís

used to balance the engine/prop/spinner combination.† Unless you are a very lucky person, by the

time you finish bolting all of that stuff together, youíre going to have an

engine imbalance the first time you fire it up.†

The DynaVibe will

tell you exactly where to place a small stack of washers on your spinner to

make it even smoother than it was before (and Corvairs are as smooth as it

gets, short of turbines).† To have your

engine balanced can cost anywhere from $150 to $400, and takes about two

hours.† I change my engine/prop

combination so often Iíd go broke in a hurry doing that, so I bought my

own.† Four or five guys (or an EAA

chapter) could buy one of these and charge $75 per balance, and it wouldnít

take long to get in the green.† More

details are at http://www.n56ml.com/dynavibe/

.

Hopefully these

experiences will give you a head start when you fly your CorvAircraft for the

first time.† To learn more about building

and flying Corvair† engines, join the

CorvAircraft email list by sending a message to CorvAircraft@mylist.net .

For more info on my

Corvair engine see http://www.n56ml.com/corvair

, and for more on my KR2S, visit http://www.n56ml.com/

.† ďBlue SkiesĒ, as they say, but cloudy

ones work fine tooÖ